Review: Joan Witek at Hunter Dunbar Projects

(ARTFORUM, by Molly Warnock) Joan Witek has been exploring the formal and emotive possibilities of the color black for roughly fifty years. In 1976, she established a studio on Duane Street, in Lower Manhattan, where Richard Serra was among her neighbors, and began working extensively with oil stick, often adding powdered graphite to the medium to vary its reflectivity and texture. This compelling survey featured thirteen paintings from 1974 to 2013 installed nonchronologically across the gallery’s two rooms. (An additional abstraction from 1969, Black Clock [Painting Number 11] —exemplary of the painter’s earlier, more gestural style—was available for viewing in the office.)

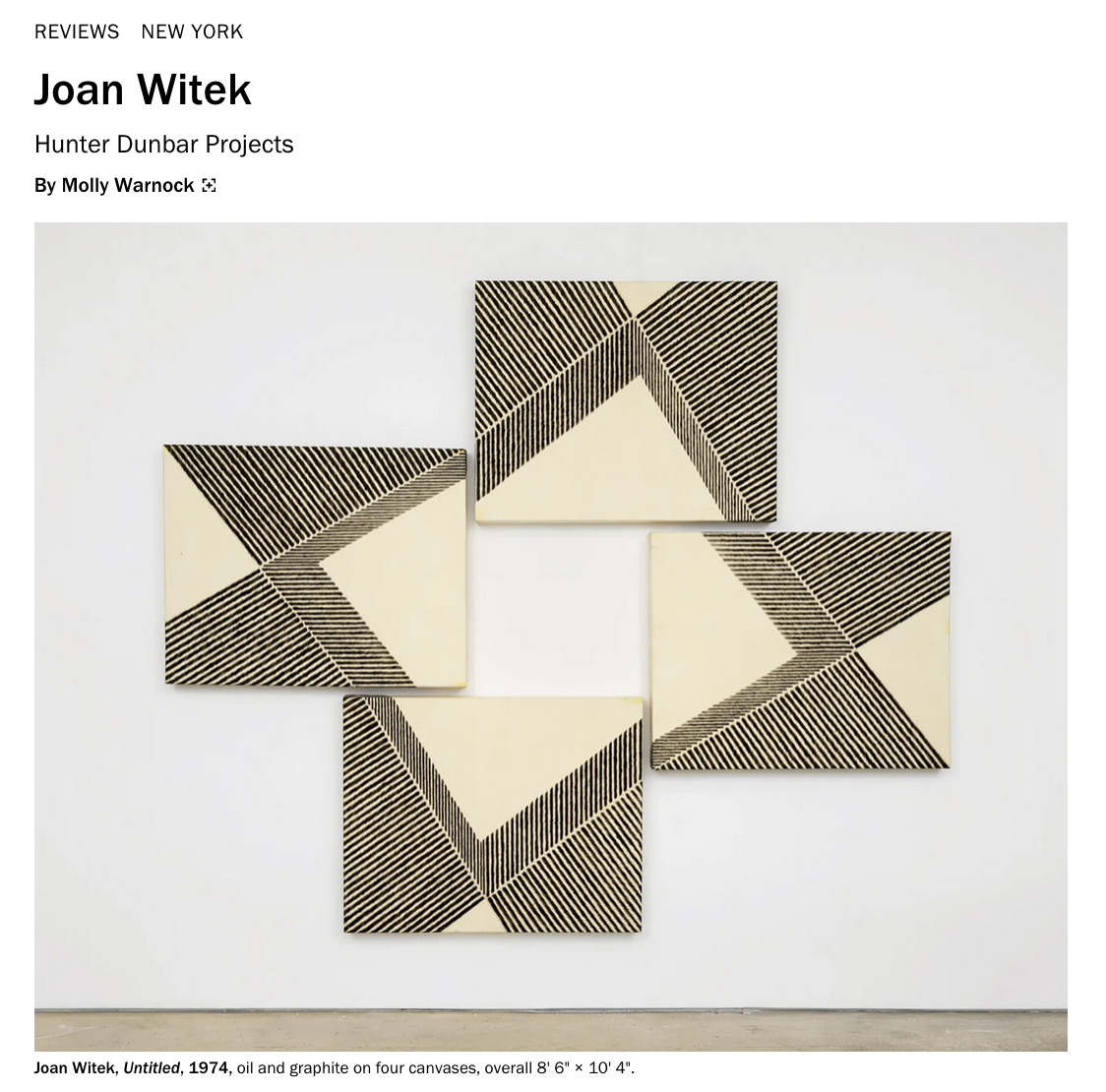

The two earliest works in the exhibition proper explored the painting’s objectness. Executed in oil and pencil, Untitled, 1974, comprised four rectangular canvases hung in a staggered, cruciate design, forming a vacant square at the center. Parallel black striations within simple geometric arrangements activated the work optically even as they underscored its physical reality. Viewed from the front, the lines generated disjunctive spatial illusions, yet they also wrapped around the panels’ conspicuously thick profiles, highlighting the work’s more sculptural aspects. Elsewhere was Untitled (Black Painting), 1976, one of a group of works that Witek produced on unstretched canvas and tacked directly to the wall. Initially, the composition appears to be an impenetrable field of densely applied black oil stick. Upon closer inspection, however, only the thinnest channels of reserved canvas, in some places already flooded by the encroaching pigment, indicate the nearly submerged axes of an open grid.

In both paintings, Witek wrests expressive effect from deliberately restrained means. Indexes of process, as in much of her work, play a crucial role. In the 1974 polyptych, the striking black-on-white patterning enfolds a more poignant interplay between the regular graphite scaffolding—clearly drawn with a straightedge and characterized by precisely measured intervals—and the subdued, almost subliminal gesturalism of the blurry strokes in oil. In the 1976 canvas, by contrast, the traces of preliminary labor—exposed lengths of pencil drawing and a blue snap line—have been relegated to the uneven margins of raw canvas about the not-quite-centered square. The plotted bounds converse quietly with the support’s wavering and slightly frayed edges, rooting artistic agency in material contingency.

Around 1980, Witek began using glyphs, as she calls them—serial black marks that reference pre-Columbian Mayan writing. The inaugural instance in this show, the sixty-eight-inch-square Prop [P(S)-5],1979, evokes Serra’s lead piece by that name: In the upper right, a smaller square containing horizontal glyphs appears at once held up and locked in place by the surrounding tiers of vertical strokes. As in the 1974 Untitled, the marks continue around the painting’s (thinner) profile, figuring the support itself as a kind of slab. Later works abandon this approach in favor of a strictly frontal presentation, shifting attention to variations within the painter’s emerging idiom. Here, Witek alters the thickness, texture, density, and orientation of the strokes; take Camouflaged by Frailties [P(S)-27], 1984, a combination of smooth oblong shapes with wider, bristling forms featuring internal clefts. She also plays increasingly with negative space: Where previously she had rubbed graphite into her supports to soften the contrast, six paintings ranging from 2006 to 2013 embraced the inherent luminosity of her gesso or acrylic grounds. Functioning at times almost as slatted screens or blinds—the metaphor is unavoidable—the glyphs here served in part to modulate that light.

Interspersed throughout the show were three more overtly gestural compositions steeped in Witek’s appreciation for seventeenth-century Spanish painting. In the front gallery, two works from 1987, in oil paint and oil stick on canvas, suggested a release of the hand amid the strictly regulated symbols. At fifty-two-by-sixty-eight inches, Laocoön [P-36] remakes El Greco’s Mannerist masterpiece at nearly identical dimensions, translating the writhing bodies and distant landscape into sinuous black lines, while P-34 displaces this evocative language to a slightly smaller vertical format. Installed in the back room was The Fable of Arachne (after Velázquez) [P-125], 2003, a sooty, towering scrim of tight, teeming marks in oil stick and Frankfurt black paint pierced by pale glimmers of canvas. Distilling the dramatic light effects at the heart of the source composition, the work is equally an allegory of Witek’s patient weaving of her oeuvre, one stroke at a time.